|

Given that I am now the

most publicly hated Muslim

in Australia, people have

been asking me how I am.

What do I say? That life has

been great and I can’t wait

to start my new adventure in

London? That I’ve been

overwhelmed with messages of

support? Or do I tell them

that it’s been thoroughly

rubbish? That it is

humiliating to have almost

90,000 twisted words written

about me in the three months

since Anzac Day, words that

are largely laced with hate.

Do I reveal that it’s

infuriatingly frustrating to

have worked for years as an

engineer, only to have that

erased from my public

narrative? That it is

surreal to be discussed in

parliamentary question time

and Senate estimates for

volunteering to promote

Australia through public

diplomacy programs? That I

get death threats on a daily

basis, and I have to

reassure my parents that I

will be fine, when maybe I

won’t be? That I’ve resorted

to moving house, changing my

phone number, deleting my

social media apps. That

journalists sneak into my

events with schoolchildren

to sensationally report on

what I share. That I’ve been

sent videos of beheadings,

slayings and rapes from

people suggesting the same

should happen to me.

Do I reassure my parents or

do I tell them the truth? I

have yet to decide.

I wrote the essay below at

the beginning of the year,

post Q&A but pre-Anzac. Even

that statement is a

reflection of the sad

reality that my life seems

to simply exist in reference

to the various outrages my

voice has caused.

Whether or not one agrees

with me isn’t really the

point. The reality is the

visceral nature of the fury

– almost every time I share

a perspective or make a

statement in any forum – is

more about who I am than

about what is said. We

should be beyond that but we

are not. Many, post-Anzac,

said the response wasn’t

about me but about what I

represent. Whether or not

that is true, it has

affected my life, deeply and

personally.

***

"Ah, the worst that can

happen is someone

sending you an angry

email. Just don’t read

it, you will be fine.

Don’t forget to take

your vitamins. Have you

checked your iron

levels? You know your

anaemia makes you

tired."

Modern-day activism does not

garner much sympathy from my

migrant parents. Looking at

it objectively it’s

something I can understand:

in Sudan the kinds of fights

they were involved in had

much higher risks. Their

friends were jailed,

tortured, killed. My mother

faced off an army who wanted

to storm her university’s

dormitory during Colonel

Omar al-Bashir’s coup of

1989. My father would

regularly tell my younger

brother and me stories of

what kind of dangers people

faced as they fought for

their political ideals.

“One of our friends was

taken by police during a

protest, for no apparent

reason,” Dad recounted one

evening at the dinner table.

“We all knew that if we did

not get him back in time, he

would be killed. So we

kicked up a huge fuss to get

him back, stormed the police

stations, got in the media …

We did not hear anything

back by the evening, and

thought that all was lost.

The next morning, the man’s

mother heard a knock on the

door. Someone had dumped a

body at the foot of the

gate, bloody and beaten

beyond recognition. It was

our friend, so badly

tortured that his own mother

did not recognise him.

Subhanallah though, he was

still alive.”

Such stories are not

uncommon for anyone who has

lived in a nation cursed by

conflict. In fact, violence

can become so normalised

that it can be an expected

consequence of pushing for

social or political change,

and there are no systems of

protection in place to

guarantee a person’s

physical safety. It’s no

wonder, then, that the

battles of a young “keyboard

warrior” in Australia do not

seem quite so serious to my

war-weary parents. Compared

with what they moved away

from, the 140-character

threats of “Twitter trolls”

seem almost quaint.

There is one major

difference, however.

Although the ideas we are

fighting for – human rights,

social justice, equality –

have not necessarily

changed, the ways those

battles are fought certainly

have. My parents’ activism

was localised, talking to

issues that at most would

affect the surrounding

region and segment of

Sudanese society. Theirs was

a fight for just governance

within a single country,

rather than an ideological

battle across nations. It

was also an analogue

challenge. The nature of

communication meant that

individual reach was limited

and therefore individual

exposure appropriately

throttled. This lent itself

to a collective front,

buffering individuals

somewhat from personal

criticism and opposition.

Today a public advocate’s

platform is digital and

greatly magnified. An issue

or debate unfolding in one

place can be amplified

through a video or tweet to

gain international support

or condemnation – sometimes

both – simultaneously. News

travels almost instantly,

and the feedback is equally

as swift. Individuals can be

rewarded with incredible

highs – a following that

spans the globe, the ability

to easily create content

that reaches millions,

membership of an online

community that “gets it” –

but also with floods of

criticism and personal,

pointed abuse.

The way this feedback is

delivered is also incredibly

isolating – abuse appears in

an individual’s inbox,

Twitter feed, Facebook page.

And while the inverse to

this – retweets, likes,

positive comments and

messages – does give some

sense of solidarity and a

collective front, that front

as a number on a screen

rather than the physical

presence of others can only

go so far towards steeling

your resolve. There is

little shared experience to

commiserate upon. Even among

those who identify with each

other, it is difficult to

convey a sense of such

personal attacks. We might

all be fighting the same

fight but we have our own

demons that divide us for

easy picking.

Furthermore, an individual’s

online presence creates a

safety concern that is

different from those

experienced by previous

generations. Whereas my

parents would have feared

government retribution in

the form of being detained,

disappeared or killed, the

threats faced by activists

and advocates today are not

nearly as organised. They

are amorphous, overwhelming

and seemingly impossible to

defend against. Imagine

every single piece of

information about you, which

you have inadvertently made

available online somehow, in

the hands of someone who

does not know you, does not

like you and does not care

what happens to you – either

a teenage hacker or a

national broadsheet – and

few rules or consequences if

that information is used

against you. It is almost

enough to terrify an

activist into silence.

Almost.

“You should just get

offline!” I am regularly

advised, after explaining

what it is like to be a

commentator in the public

space, advocating for

ludicrous concepts such as

the right to be heard or the

seemingly radical ideal of

equality. Asking us to go

offline is like asking us to

leave the streets. Sure,

it’s the safe thing to do,

but it ignores the

importance of the online in

any struggle today. The

online and offline worlds

are inextricably linked; in

2017 they are simply

different dimensions of the

same reality.

***

I learnt these realities in

a baptism of fire in

September 2016 after I

walked out of a speech and

accidentally picked an

ideological fight with a US

woman who is an important

literary figure. What I did

not realise at the time was

that this is something a

young, brown Muslim woman

simply must not do,

particularly if the conflict

is even vaguely connected to

the nebulous concept dubbed

“identity politics” – a

phrase coined, seemingly, to

dismiss or disregard anyone

asking for their oppression,

historical context or

personal reality to be

recognised and respected.

How silly of me to miss the

memo. Respect is so passé.

I shall spare you the

details; googling “Lionel

Shriver Yassmin Abdel-Magied”

should be enough to keep you

entertained for hours. Put

simply, I had flown a little

too close to the sun. I’d

been given my wings, told I

could fly with the flock and

contribute to the discussion

as an equal, told I could be

a part of “us”. No one

mentioned the feathers were

fixed in place with wax, and

the sun wouldn’t hesitate to

strip them away.

Walking out, and then

writing an (admittedly)

emotionally charged piece

about my reasoning, led to

an unexpected – and global –

ideological hammering.

Criticism and ad hominem

attacks were levelled from

all over the world, starting

with Australia’s national

broadsheet and stretching

all the way to the New York

Times.

Not only was the outcry

deafening but the commentary

it unleashed was merciless.

Breitbart, the (fake?) news

site and platform of the

“alt-right” – formerly

chaired by Steve Bannon, now

Donald Trump’s chief

strategist – featured an

article on the encounter. It

was not as cruel as it could

have been, if I’m honest.

But it was certainly deeply

convinced of its own

righteousness:

‘Everyone’s entitled to

their opinion’ … But if

that opinion happens to

be so ill

thought-through, poorly

argued, whiny, needy,

constrictive, selfish,

ugly, ignorant, flat out

wrong and probably quite

dangerous too, then they

deserve to be called on

it and relentlessly,

mercilessly mocked till

they never spout such

unutterable bollocks

ever again in their

special snowflake lives.

I had messages from friends

in India, Italy and

Indonesia whose friends and

family had been discussing

the affair. For a brief

moment it became the topic

of dinner-table

conversation. The result of

that spotlight though meant

that for the next three or

four weeks my life was

overwhelmed by this story. I

had hundreds of emails a

day, to the point where I

began to automatically

delete them and avoided my

multiple inboxes completely,

to the chagrin of those who

were trying to connect for

non Shriver-related

business. I deleted Twitter

from my phone, deactivated

Facebook and wrote almost

nothing online for an entire

month. Which, for me, is a

pretty long time.

But because the online is

not truly separate from the

offline in our lives, it

wasn’t truly an online coma.

The modern-day equivalent of

a pack of citizen paparazzi,

perhaps, were still on the

front lawn, constantly

slipping notes under the

door, knocking on the

windows, yelling

obscenities. While I

couldn’t hear or see them, I

knew they were there.

For a modern-day “social

justice warrior”, as we are

often pejoratively named,

being attacked online comes

with a sense of being

desperately alone. It was me

and a glowing screen, the

dings of messages, tweets,

emails sent by strangers

reminding me of my place in

the world.

Drip by drip, message by

message, it’s the Chinese

water torture of the online

age.

***

The weeks rolled by. The

influx of messages

eventually slowed and a

semblance of normality was

restored. It seemed the

storm had passed.

Months later, at the Jaipur

literature festival, I

bumped into another

important literary figure.

Tall, imposing and very

British, he was the type of

high-level agent who

wouldn’t normally bother

with someone like me – save

for the fact that I too am

tall, and our eyes met

briefly as he crossed the

lawn. He slowed as he

approached me, then stopped

as his face brightened.

“Oh, I know you,” he said.

“You’re the girl they’re all

talking about!” I assumed he

was referring to the elite

group of global literary

stars gathered at the

writers’ party that evening.

“Good things, I hope?” I

said, glibly.

His response was emphatic

and, in a typical English

fashion, faintly apologetic.

“Oh, no, no, I’m afraid not.

They all disagree with you,

really.”

“Oh!” I feigned shock,

though of course I was very

well aware. The next line

was much more genuine: “I do

wish they would disagree to

my face! I would love to

have a conversation with

them.”

The agent shook his head. It

was late and he looked

slightly intoxicated, which

was probably why he was more

forthright than Englishmen

usually seem to be.

“Oh, no, no one would do

that. You’re very

intimidating! We’re all a

little frightened of you.”

I flashed my biggest,

pearliest smile and pointed

at my teeth. “Look at this

face, hey? How could I

possibly be intimidating?”

But it seems there is

something incredibly

intimidating about a young,

brown Muslim woman who is

unafraid to speak her mind.

This became clear again in

February 2017 when I was

invited to join a panel

discussion on the ABC’s Q&A.

You may have seen the video

– after all, it took only a

week for the clip to reach

12 million views on

Facebook. In essence, I

challenged Senator Jacqui

Lambie’s views on sharia and

Islam, loudly and

passionately. The immediate

response online was

incredibly positive,

bolstering my confidence –

but that was short-lived. My

head above the parapet, I

then became the subject of a

strange and unnecessary

character assassination by

the national broadsheet.

“This is it,” I thought.

“I’m never going to get a

corporate job again. Who

will employ me after the

things that have been said?”

But this time around, I

would be pleasantly

surprised. Within a week,

voices of support made

themselves heard: radio

presenters challenged the

criticisms levied against

me, breakfast show hosts

defended my reputation, and

much ink was spilled in

calling out the bullying and

canvassing for a more

considered and egalitarian

response. I could not

believe it, to be honest:

the articles and columns

laced with hatred I had come

to expect – but others

putting themselves on the

line to offer their support?

It was a humbling and

fascinating experience.

Perhaps, on reflection, I

was not in this alone after

all.

***

The irony in all this, of

course, is that I am no one

very important. I do not

hold an elected office, I do

not officially represent any

racial or cultural group,

and I have never been part

of a political party, union

or even political student

organisation. I am a

25-year-old Muslim

engineering chick, born in

the Sahara desert, whose

words occasionally find

themselves in the public

arena. And if a few words

that I put together are

enough to terrify

institutions into attacking

me, stumbling over

themselves to demonstrate

why “people like her” are

wrong and why we should not

be listened to because our

words are oppressive, then

one has to ask, what are

they so afraid of? Why are

they so afraid? For if the

argument was truly as

irrelevant as so many claim

it to be, then surely it

wouldn’t be worth all this

energy.

Today’s identity politics

are about power – but not

“real” or “traditional”

power. The reality is, real

power – that which lies in

financial resources, the

mainstream media and

politics – is held by hands

similar to those of 50 or

100 years ago: white, male

hands. Not much has changed.

Sure, there are several

women and people of colour

fighting the fight, and many

more making their way up the

ranks, but look at the true

hallmarks of power. Who owns

the media companies,

controls the big corporates,

runs the countries? If the

real, hard stations of power

are still in the hands of

those who have always had

it, why are they so worried?

Part of me suspects that the

reason these attacks are so

vitriolic, swift and

all-encompassing is because

they are about identity.

Identity politics is

personal, and that’s why

people take it so

personally. By asserting my

identity in a way that

challenges my “place in the

world”, I inadvertently

challenge the place of those

who feel entitled to their

privilege and status. That

feels not only wrong to such

people, but deeply,

personally offensive –

because what is at stake is

who they are in the world.

And so they fight viciously,

because if privilege and

status and wealth and

whiteness define who they

are, what else could be more

valuable?

Those who lack a definitive

“place” in society have

little to lose by calling

out injustices and

structural inequalities, and

much to gain by disrupting

the status quo. For those

with something to lose in

that disruption, this can be

a terrifying prospect. For

everybody else, it is a

reminder of the strength and

conviction that is needed to

fight for a more just world.

On that, my parents and I

agree.

• This is an edited extract

from Griffith Review 56:

Millennials Strike Back

The Guardian

Despite the rhetoric,

here's why Islamophobes

don't want Yassmin to go

By Randa Abdel-Fattah

It's 2018, and every Muslim

in Australia has been

interned. The "radicals",

the "moderates", the devout,

the nominal, the

Aussie-born, the migrants,

the Logie winner, the TV

hosts, the Q&A guests. The

lot. Australia is now a

Muslim-free country.

Has Islamophobia won? Well,

no. Because despite the

rhetoric and hysteria, this

is precisely what

Islamophobia does not want.

You see, Islamophobia needs

Muslims. Not because it

"needs an enemy". But

because Islamophobia is

driven by the same logics

that define patriarchy.

This is very different to

saying that Islamophobia is

about hating Muslims. If

only it were that simple.

Think about how much easier

it is to challenge misogyny

– hatred of women – than it

is to challenge patriarchy –

a society structured on male

domination, privilege and

control. In the patriarchal

utopia, women are not

removed from society, but

they exist within a space

that seeks to contain,

groom, control and possess

them.

This, too, is the goal of

Islamophobia, and nothing

has demonstrated its

internal patriarchal logic

more clearly than the

treatment of Yassmin Abdel-Magied

– who, after weathering

months of intense

Islamophobic backlash, drew

further ire this week when

she announced she's decided

to leave the country.

Abdel-Magied has come to

represent everything that

Islamophobia hates – but

actually loves– about "the

Muslim problem". It's a game

of seeing how far "the

Muslim" can be controlled

and disciplined. Like men

who enjoy asserting power

over women's lives, there is

a perverted pleasure in this

exercise of seeking to

dominate Muslim lives –

telling Muslims how and

where to dress, speak, eat,

worship, and live.

The SMH

Channel 7 removes

‘hateful’ poll over Yassmin

Abdel-Magied’s decision to

leave the country

CHANNEL 7’s digital arm has

“unreservedly” apologised

for publishing a now removed

Facebook poll asking

followers to vote on whether

the Muslim activist Yassmin

Abdel-Magied should leave

the country or “face her

critics”.

The poll, posted on the 7

News Australia Facebook

page, was slammed by

followers and commentators

for inciting racist

discussion and bullying, and

Ms Abdel-Magied herself said

it invited “prejudice and

discrimination”.

After being questioned by

news.com.au, the station

removed the poll from and

admitted it “should never

have been posted”.

Yahoo7, which administers

the 7 News Australia

Facebook page along together

with Seven News, has since

taken responsibility for the

post.

The Facebook post published

Tuesday asked followers to

comment on Ms Magied’s

decision to leave Australia.

The controversial television

presenter and commentator

recently announced she was

moving to London after being

“traumatised” over facing

what she described as

“deeply racist” criticism.

The engineer-turned-media

personality has been

constantly criticised since

posting an insensitive

comment on Anzac Day which

she removed from her page.

Seven’s post shared the news

that Ms Abdel-Magied had

announced she was leaving

Australia and posed the

question: “Do you support

her decision to move to

London or do you think she

should stay and face her

critics?”

The post attracted more than

1600 comments and 17,500

votes, according to

Facebook.

In an update

published overnight 15 per

cent of respondents had

voted “no” and 85 per cent

has voted “yes”.

While many respondents were

critical of Ms Abdel-Magied,

an outspoken Muslim who has

defended her religion

publicly, a lot of

commenters hit Seven with

accusations of “bullying”

over the decision to publish

it and invite “racist” and

“vitriolic” discussion”.

“You need a third option

“this shouldn’t even be

polled,” Laura Jane wrote.

“This is awful. Why would

you think it was acceptable

to poll people on Yassmin’s

decision to move to London?

Particularly in light of the

relentless racist vitriol

that she’s copped that 7

News Australia is

contributing to,” Sophie

Trevitt wrote.

“As a media outlet, you

don’t think you have any

ethical and professional

responsibilities? Check out

the comments below.”

Liam O’Reilly wrote: “FFS 7

news stop perpetuating hate

for clicks!

In an email

to news.com.au, Ms Abdel-Magied

said she considered the post

a poor publishing decision.

“This is more a reflection

of Channel 7’s poor

editorial decision-making

than anything else,” she

said.

“The outlet’s profiling of

me in this way invites

prejudice and

discrimination. It’s pretty

trashy click-bait.”

A spokeswoman for Channel 7

told news.com.au the

situation was being

investigated.

“The poll have been removed.

It should never have been

posted and we are reviewing

how that occurred.”

News.com.au has since

received a statement from

Yahoo7 apologising for the

post.

“The poll

regarding Yassmin Abdel-Magied

was posted by the Yahoo7

online news team, which

administers the 7News

Australia Facebook page,

together with 7News,” the

statement read.

“It was posted to genuinely

create discussion around a

balanced article and it was

never the intention to

generate inappropriate

commentary on social media.

“We accept this was an error

of judgment, the post has

been removed and we

unreservedly apologise to

anyone offended.”

News.com

Why Yassmin Abdel-Magied

Had To Be Destroyed

Moderate,

educated, and articulate

young Australian-Muslims

contradict the

generalisations of

Australia’s growing

Islamophobic current, writes

Max Chalmers.

***

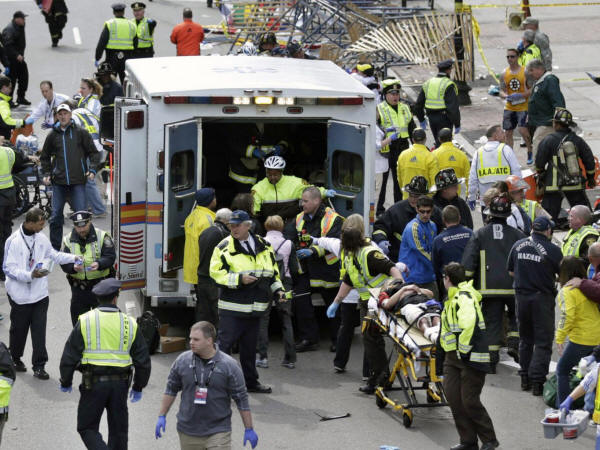

For this

burgeoning sector of the

country, the apparition of a

Muslim who looks like

anything other than a

suicide bomber is a scandal.

It contradicts their varied

assertions about the true

evil of Islam, and the

universal untrustworthiness

of Muslims. This growing,

increasingly paranoid

audience have had their

preconceptions so heavily

groomed that any

contradiction becomes an

outrage.

That’s one reason why the

drawn-out and orchestrated

demise of Abdel-Magied has

been so unpleasant to watch

from afar [Ed’s note: Max

Chalmers is now based in the

US].

The

appearance of the ‘moderate

Muslim’, the personage that

newspapers like The

Australian insist they will

tolerate, cannot be allowed

to stand.

“The scale [of the response]

would suggest Yassmin outed

herself on the program as a

paedophile or a North Korean

spy,” Susan Carland wrote

after Yassmin Fury Round

One.

Then, on Anzac day, Abdel-Magied

posted: “LEST. WE. FORGET

(Manus, Nauru, Syria,

Palestine)”. The post was

quickly removed and the

author apologised.

Again, very few responders

actually bothered to put

forward an argument

explaining why this (very

ambiguous) post was

offensive, moving straight

to calls for Abdel-Magied to

be punished. There was a

glee about it. Finally,

something to hang her with.

As the attacks maintained

their pace, their obsessive

tracking of Abdel-Magied’s

movements, their hysteria, a

federal senator eventually

declared the young

Australian should “move to

one of these Arab

dictatorships that are so

welcoming of women.”

As Carland argued, Abdel-Magied’s

critics – the ones who

insist, ‘no no, it’s

behaviours and ideas, not

identities, that we oppose’

– had unmasked themselves.

“It

finally puts into full

technicolour display the

truth of their feelings

towards Muslims: that the

only acceptable Muslim is a

non-Muslim.”

“Many Muslim women avoid the

media, think twice about

public interventions because

the personal cost is so

vicious and so high,”

Abdel-Fattah noted.

“Many Muslim women avoid the

media, think twice about

public interventions because

the personal cost is so

vicious and so high,”

Abdel-Fattah noted.

As with Abdel-Magied, you

may well object to a

particular position held by

Aly. But it is only by

virtue of his religious

identity that he could ever

be treated as truly

outrageous by so many. And

it is only by virtue of his

liberal beliefs, articulate

nature, successful

integration, and handsome

televisual image that his

identity could cause such

burning fury.

He is worse than the

extremist. He is the

moderate who thinly-veiled

Islamophobes have insisted

they will accept.

With the ferocity and fury

that have been unleashed,

it’s easy to forget just how

absurd the situation is.

Abdel-Magied has

consistently put forward a

familiar critique of

Australia as a nation that

has failed to represent and

respond to all of its

inhabitants and has

committed historical wrongs

as a state. She adds a kind

of identity politics to

this, a way of thinking now

intuitive to many younger

Australians especially.

You may take issue with this

worldview or ideological

bent, but you can’t deny it

is drawn from mainstream

currents.

In a

society that bills itself as

open, Abdel-Magied should

have the right to make

radical and even extremist

critiques. As it turns out,

however, she does not.

Migrants do not have to take

the path of Abdel-Magied.

The process of immigration

is one that may take

generations to settle. It is

a tumultuous transformation.

People need to be given the

room to acclimatise, to make

paths for themselves on

their own terms.

But that is not the path

Abdel-Magied has chosen. She

has rapidly joined the

mainstream conversation and

been unafraid to assert her

identity, on her own terms.

She has taken a few steps

down the well-trodden paths

of Australia’s culture wars.

She has not functioned

purely as a spokesperson to

denounce her own non-white

community.

And

worst of all, she hasn’t

done anything unethical or

outrageous in the process.

That’s a crime a growing

number of Australians cannot

abide.

New Matilda |