|

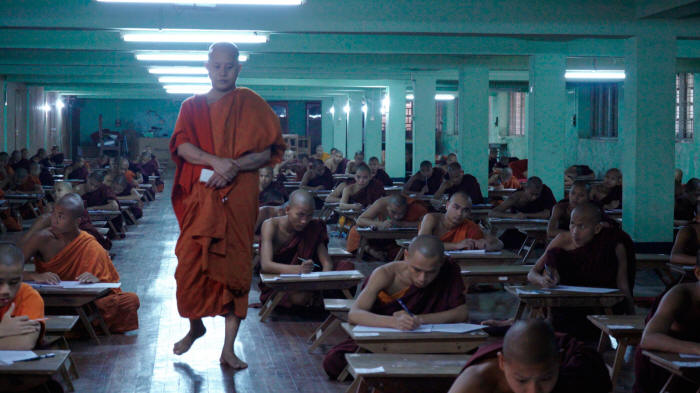

Ma Soe Yein is the largest

Buddhist monastery in

Mandalay, Myanmar. A dreary

sprawl of dormitories and

classrooms, it is located in

the western half of the

city, and accommodates some

2,500 monks. The atmosphere

inside is one of quiet

industry. Young men, clad in

orange and maroon robes, sit

on the floors and study the

Dharma or memorize ritual

texts. There is little noise

except for the endless

scraping of straw brooms on

wooden floors, or the

dissonant hum of people in

collective prayer. Outside,

the scene is livelier. Monks

hurriedly douse themselves

with cold water, and chat

politics over a table of

newspapers. They do so in

the shadow of a large wall

covered with gruesome images

depicting the alleged

bloodlust of Islam.

Photographs, displayed

without any explanation or

evidence of their origins,

show beaten faces, hacked

bodies, and severed

limbs—brutalities apparently

committed by Muslims against

Myanmar Buddhists.

The contrast between the

monastery’s inner calm and

this exterior display of

violence is a fitting

inversion of Ma Soe Yein’s

most infamous resident,

Ashin Wirathu, the subject

of Barbet Schroeder’s new

documentary, The Venerable

W. On the outside, Wirathu

is composed and polite, with

large brown eyes and a

sweet, impish grin. His

voice is smooth and its

cadence measured. Yet

beneath this civil disguise

seethes an interminable

hatred toward the 4 percent

of Myanmar’s population that

is Muslim (the wall of

carnage stands outside his

residence). Wirathu is

responsible for inciting

some of the worst acts of

ethnic violence in the

country’s recent history,

and was described by Time as

“The Face of Buddhist

Terror.”

|

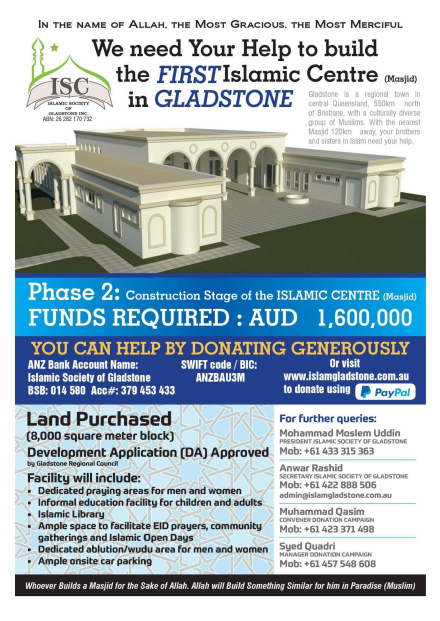

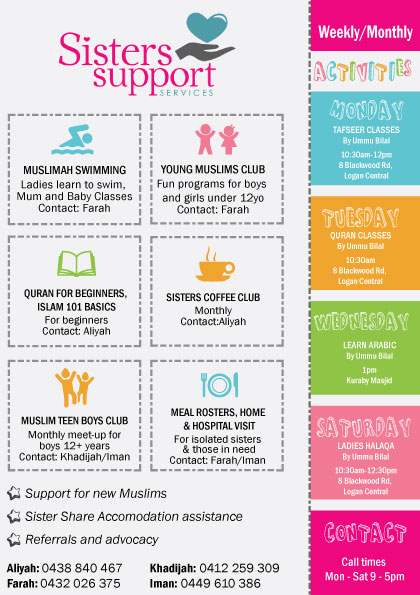

A wall covered with images

depicting the alleged bloodlust

of Islam at the Ma Soe Yein

Buddhist monastery, from The

Venerable W., 2017 |

Schroeder, an Iranian-born

Swiss filmmaker, has spent

decades documenting the

morally despicable. His

“Trilogy of Evil” began in

1974 with General Idi Amin

Dada: A Self Portrait, a

character study of the

Ugandan dictator. The second

installment, Terror’s

Advocate (2007), was on the

French-Algerian defense

lawyer Jacques Vergčs, whose

clients have included Klaus

Barbie, Carlos the Jackal,

the Khmer Rouge leader Khieu

Samphan, and the Holocaust

denier Roger Garaudy.

Wirathu is Schroeder’s final

subject, and, for him, the

most terrifying. “I am

afraid to call him Wirathu

because even his name scares

me,” he said in a recent

interview with Agence

France-Presse. “I just call

him W.”

The film charts Wirathu’s

rise from provincial

irrelevance in Kyaukse to

nationwide rabble-rouser. It

centers on the crucial

moments of his budding

ethno-nationalism, such as

in 1997, when he says his

eyes were “finally opened”

to the “Muslims’ intentions”

after reading a pamphlet

entitled In Fear of Our Race

Disappearing, which appeared

in print by an unknown

author; or 2003, when he

delivered a chilling

sermon—caught on

camera—against Muslim

“kalars” (kalar is the

equivalent of “nigger”). “I

can’t stand what they do to

us,” he says to rapturous

applause. “As soon as I give

the signal, get ready to

follow me…I need to plan the

operation well, like the CIA

or Mossad, for it to be

effective…I will make sure

they will have no place to

live.” One month later, in

Kyaukse, eleven Muslims were

killed, and two mosques and

twenty-six houses were

burned to the ground.

Wirathu was arrested by the

military junta for inciting

violence, and spent nine

years in Mandalay’s Obo

prison.

|

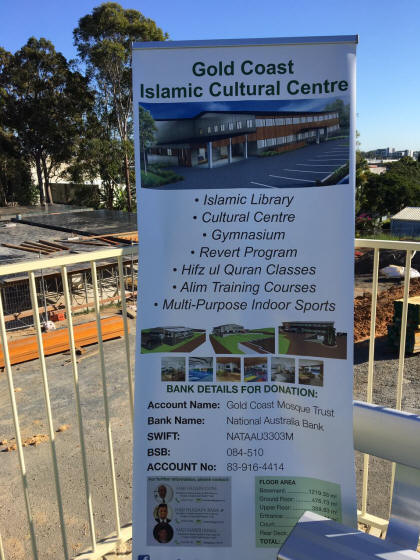

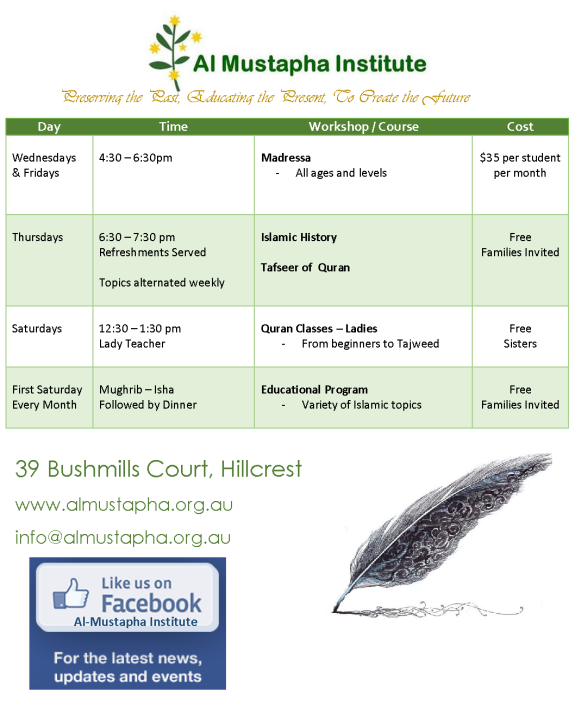

The remains of a mosque in

Meiktila, central Burma, after

the March 2013 anti-Islamic

riots, from The Venerable W.,

2017 |

Like Marcel Ophüls, a

filmmaker who explored the

quotidian aspects of

intolerance and oppression,

Schroeder’s interviewing

style is never hostile or

moralistic. As he writes in

the notes to the film, the

point is to let the subjects

speak, “without judging

them, and in the process

evil can emerge under many

different forms, and the

horror or the truth comes

out progressively, all by

itself.” In one instance,

Wirathu bares the depths of

his self-regard when he

claims to have been the

inspiration for the Saffron

Revolution of 2007—a

delusion scorned in the film

by one of its leaders, U.

Kaylar Sa, who describes the

desperate social conditions

that forced the monks onto

the streets of Rangoon.

Wirathu was freed as part of

a general amnesty for

political prisoners in 2012,

and he quickly went on to

revitalize the 969

Movement—a grassroots

organization founded earlier

that year by Wirathu and

Ashin Sada Ma, a monk from

Moulmein, and committed to

preventing what it sees as

Islam’s infiltration of, and

dominance over, Buddhist

Myanmar. Since 2014, Wirathu

has operated under the

auspices of the Ma Ba Tha,

or Organization for the

Protection of Race and

Religion. Like 969, many

members of the Ma Ba Tha

spread propaganda about how

Muslims steal Buddhist women

and outbreed Buddhist men.

“The features of the African

catfish,” Wirathu tells

Schroeder near the beginning

of the film, “are that they

grow very fast, they breed

very fast, and they’re

violent…The Muslims are

exactly like these fish.”

W. is tougher viewing than

its predecessors. Archival

material and scenes

Schroeder filmed undercover

are spliced with footage

from YouTube and Facebook

captured on camera phones

and personal video

recorders. Most of this

documents atrocities

committed in Rakhine state

in 2012—when clashes between

ethnic Arakanese and

Rohingya Muslims forced

125,000 of the latter into

displacement camps—and

anti-Muslim riots in central

and eastern Myanmar in 2013.

There are graphic images of

burning homes, men beaten to

death with wooden clubs, and

people left to burn alive.

All the while state police

stand back and let it

happen—Amartya Sen has

called the violence

committed against the

Rohingya a “slow genocide.”

Using video uploaded to

YouTube and Facebook helps

convey one of Schroeder’s

most important points about

Wirathu. What was

frightening about Idi Amin

was his combination of

absolute power and

volatility, a man whose

dormant rage erupted without

warning. With Jacques Vergčs,

it was his gifts of

seduction and dexterity of

logic that made him

something like Woland from

Bulgakov’s The Master and

Margarita—a Devil with

impeccable tailoring. What’s

disturbing about Wirathu is

how, as one anti-Wirathu

monk puts it, he wants

people to “experience his

words before accepting

them.” The aim of his public

sermonizing is to transform

the impressionable into

unthinking agents of his

intolerance, which accounts

not only for his

call-and-response style of

preaching, and the fact

that, as the film shows, he

regularly instructs

children, but also for his

extensive use of Twitter and

Facebook, and the

Islamophobic

DVDs he produces and

distributes throughout the

country. Like his favorite

politician, Donald Trump—the

only presidential candidate,

he says in the film, who

will prevent Islam’s global

domination—Wirathu both

channels and reflects the

ways in which social media

has transformed hate into a

thoughtless pastime. His

evil, an attempt to deepen

and normalize the mores of

racial enmity, might be

encapsulated by a line from

Byron, which serves as an

epigraph to the film: “Now

hatred is by far the longest

pleasure;/ men love in

haste, but they detest at

leisure.”

This is an important

documentary that not only

illuminates the rank

underbelly of Theravada

Buddhism in Myanmar, but

also captures one of the

first major tests faced by

the new political order,

especially regarding freedom

of speech and assembly.

Wirathu is a thorn in the

side of a Suu Kyi government

that is trying to end a near

seventy-year civil war and

rebuild the country after

decades of economic

catastrophe. A question many

of those in government must

surely (hopefully?) be

asking is, “Who will rid us

of this turbulent priest?”

In the short term, it is

unlikely to be the monks

themselves. Although

Myanmar’s official Buddhist

authority—the Ma Ha Na—has

banned the Ma Ba Tha from

using its full Burmese name,

it has not addressed the

group’s discriminatory aims

and activities. This is

partly to do with the

widespread support enjoyed

by the Ma Ba Tha, which

builds Sunday schools,

provides legal aid, and

raises money for charities.

The state of race relations

in Myanmar is far more

complex than Schroeder’s

film allows. It is not

uncommon to hear members of

the Bamar majority say they

“hate Islam” but, when

pressed, admit they have no

issue with Muslims living in

their towns. One of the

film’s other blind spots is

the military. Aside from a

brief glance at the mass

population shifts between

Rakhine and Bangladesh in

the late 1970s, there is

very little on how the army

had been inciting ethnic

violence in places like

Rakhine long before Wirathu

appeared, nor is there any

mention of a popular theory

that Wirathu is paid, or at

least encouraged, by senior

generals, some of whom are

often photographed at his

monastery. In this lack of a

deeper historical setting,

and the argument that the

film could have gone further

to expose the involvement of

the military in ethnic

violence, Schroeder’s film

resembles Joshua

Oppenheimer’s harrowing

documentary The Act of

Killing (2012), which

examines former members of

the Indonesian death-squads

responsible for the mass

killing of communists

between 1965-1966.

A greater problem with The

Venerable W., and the

“Trilogy of Evil” as a

whole, is how Schroeder

assumes evil to be a given

in the world. He is the

filmmaker’s Kolakowski,

someone who believes evil

isn’t rooted in social

circumstance, but is a

permanent feature of the

human condition. Only the

concept of “evil” can

capture the immoral

extremities reached by

figures like Amin, Vergčs,

and Wirathu. But there is

little sense in W., or in

the other two films, of

evil’s potential origins, or

how Wirathu’s ideas may have

formed and why they are

admired in places like

Maungdaw in Rakhine, where

there has been historical

tension between Muslims and

Buddhists, but less so in

Yangon or Mandalay, where

there has not. Imploring us

to think of evil without

considering what it means

does little to illuminate

the darker side of human

behavior. As the American

clergyman William Sloane

Coffin put it: “Nothing is

easier than to denounce the

evildoer, and nothing is

more difficult than to

understand him.”

Barbet Schroeder’s The

Venerable W. is playing at

Telluride Film Festival

(September 1 through 4),

October 13 and 14 at the New

York Film Festival, and

October 13 and 15 at the

Mill Valley Film Festival.

Source:

NYBooks

|

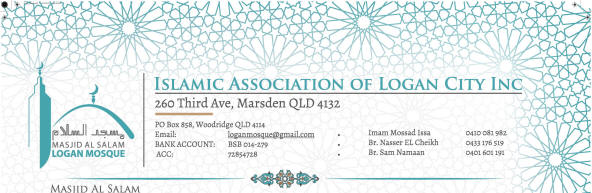

Leaders

of the Australian Federation

of Islamic Councils, also

known as AFIC, have drafted

an extraordinary letter to

Turkish President Recap

Tayyip Erdogan.

Leaders

of the Australian Federation

of Islamic Councils, also

known as AFIC, have drafted

an extraordinary letter to

Turkish President Recap

Tayyip Erdogan.