|

A tall young man with warm

brown eyes walks across the

soft Persian carpet of a

Melbourne mosque, smiling.

Imam Alaa El Zokm stands

almost two metres, and in

his long, grey clerical

robes seems even taller, as

though his height were a

conscious decision –

something to help better

watch over all 600 people

here at the Elsedeaq Islamic

Society in suburban

Heidelberg Heights.

The building sits on a

corner surrounded by

weatherboard houses, and

right now old men and tiny

boys and taxi drivers on

lunch break – a mix of

Egyptians, Somalis and

Australians – are stopping

in for the imam's khutbah or

Friday speech, the Muslim

equivalent of a Sunday

sermon. They shake his

large, soft hands, and nod

to one another. They pick up

copies of Australian Arabic

newspaper Al-Wasat, glance

at the headline ("The

Climate of Fear that Divides

Australian Society") and

skim ads for camel milk and

sharia-compliant

investments.

|

Imam Alaa El Zokm likens some

people's fear of Muslims to a

fear of snakes - snakes that are

more afraid of you than you of

them, and that are rarely

encountered. |

We meet at the mosque some

time before new US President

Donald Trump issues an

executive order targeting

citizens from seven

predominantly Muslim

countries, creating

international outrage. The

imam has been advising his

flock not to worry about

Trump, not as "much as we

should about ourselves".

When news breaks of the

order, I call him. He says

he is not angry or even

confused by Trump's latest

attack on Muslims, but

instead disappointed. "And

unfortunately we hear the

same thing from some people

in Australia, like Pauline

Hanson. It is taking us back

to an age of darkness. This

is something against

humanity."

The people who come to his

mosque are mostly from

Somalia, one of the seven

countries identified for

"extreme vetting". He tells

me that they came

immediately to him, seeking

comfort. "They are

frightened," he said. "But I

tell them that the majority

of the American people are

educated and good, and

renounce racism, and want to

live in a peaceful society,

and are against this

decision. I tell them I have

hope."

But on this day long before

the Trump inauguration, it

is a regular day at the

mosque. It fills until the

hall is bursting, as are the

ante-rooms, carport and the

lawn outside. The women and

girls sit upstairs in a

balcony behind a fabric

veil, listening to his words

on a closed-circuit TV loop.

Among the crowd is Abdi

Alasoo, 50, a retired

scaffolder and part-time

Uber driver who left Somalia

30 years ago "with $100 and

a one-way ticket".

I ask how he likes the young

imam, who is 27 and has been

with the mosque two years,

and whom I plan to follow

for three months to see what

it means to live at the

centre of an Islamic

community in Australia.

Before Alasoo can answer,

the imam overhears and

offers his own

self-assessment: "Good. Very

good," the imam says,

laughing and waving. "You

say, 'The sheikh is very

good.' I will pay you!"

Alasoo says as much anyway.

The whole flock does.

"Sheikh Alaa," they say,

knows Islam, speaks English,

is highly educated, and he

is moderate. "He says it is

our job to convince others

that what the people say,

the media says, the

terrorist says, is not us,"

says Alasoo. "We have to

show more of that good

thing."

In the mornings, afternoons

and late nights I spend with

the imam, he has many

avenues for spreading his

message. As a spiritual

adviser, of course, but also

as a school teacher,

marriage counsellor and

confidant – mediator of

business rifts and settler

of personal quarrels. The

imam is the man his

congregation can turn to at

any hour, with a Facebook

message or pre-dawn phone

call or a knock at the door

near midnight, which they do

with a torrent of questions

and problems for him to

reconcile.

His wife, 21-year-old Rheme

Al-Hussein, says they call

from his native Egypt, too,

all through the night. He

exists on coffee with milk

and two sugars. "I feel

sorry for him sometimes,"

she says. "At the end of the

day I can tell when he's not

there, when I'm talking to a

wall."

He stands now inside the

mihrab, a semicircular wall

cavity that faces Mecca. The

crescent-shaped

architectural feature can be

found in most mosques and

once acted as a kind of

amplifier. In the new

millennium, a headset

microphone will do. He prays

now, eyes closed, shoulders

rising and falling as he

takes deep gulps of air to

sing each undulating phrase.

And then he ascends the

minbar – a raised platform

of timber steps – to a seat

like a throne. (The imam

tells me later that this is

not merely to elevate him in

the eyes of others. "It is

also for the imam himself,"

he says. "When he goes up,

he should know that he is a

role model for everyone,

that his sayings must match

his actions.")

The sayings in this speech

come in a passionate Arabic

flurry. Afterwards, he

repeats the same in

developing English. "We must

address the Islamophobia!"

he says. "People are afraid

from the Islam. They see

Islam and see the terrorist.

They see Islam and they see

the mistreatment of the

women. They see Islam and

they see the jihad. But as

the Prophet said, the most

important jihad is the jihad

within! It is the jihad

against hatred, and the

hardened heart."

He likens a fear of Muslims

to a fear of snakes – snakes

that are more afraid of you

than you of them, and that

are rarely encountered. A

recent Ipsos Mori poll found

that while the Muslim

population of Australia is

little more than 2.4 per

cent, Australians on average

believe the religion

accounts for 18 per cent.

Furthermore, an Essential

Research poll recently found

49 per cent of Australians

would support a ban on

Islamic immigration, citing

perceived concerns over

terrorism and Muslims

failing to share Australian

values. Another study found

60 per cent would be

"troubled" by a relative

marrying a Muslim.

“I tell [my community] that

the majority of the American

people are educated and

good, and renounce racism,

and want to live in a

peaceful society, and are

against this decision. I

tell them I have hope.”

"We must reach out. We

must!" he pleads. "It is our

responsibility – to make

friends with the non-Muslim,

to show them who we are, so

that when something bad

happens they can point to us

and say 'No! This is my

friend! He is Muslim and he

is not like this – this is

not what he believes.' We

must be role models."

|

Imam Alaa El Zokm at the

Elsedeaq Islamic Society in

Melbourne's Heidelberg Heights.

|

Alaa El Zokm sits on a white

leather couch in his yellow

brick veneer home opposite

the mosque. Hussein hands me

a plate of orange wedges,

strawberries and mango, then

sits down. Zokm reaches

across, touches an eyelash

off his wife's cheek, and

blows it away.

They have an easy rapport.

No kids yet. Hussein is

focused on school. In her

third year of a master's

degree in speech pathology,

the workload is heavy.

They met almost three years

ago when the imam first came

for a visit from Egypt,

invited here to consider a

position with the mosque and

a school. "I didn't know

anything about Australia,"

he says. "Nothing. The end

of the earth? Kangaroos?"

His hosts then were wary for

the imam, worried that the

religious leader would

explore Australian streets

and be confused or upset

when passing a raucous

corner pub or a Victoria's

Secret store. He watched

American movies growing up,

however, and so the culture

shock was not so extreme,

even though he remains

steadfast on matters such as

drinking or sex before

marriage. "It's very clear,"

he says. "It's not allowed.

In any way."

Near the end of his trip,

the imam was invited by a

sheikh to meet two local

girls. The Lebanese one, he

was told, was more

religious, and the Egyptian

one more beautiful. Who did

he want to meet?

The imam was stunned. He

went along to a home in

Melbourne's north, however,

and the Lebanese girl was

there, being taught the

Koran. She was shy and did

not look at him. He didn't

look at her, either. They

both giggle at the memory.

"It was very funny!" says

Hussein. "We didn't even

meet! It was so weird. He

was here for three weeks and

going back to Egypt. I was

only 18."

They both thought and

prayed. Hussein had always

wanted to marry an Islamic

leader, and the imam knew

marriage could be

advantageous. "The imam is

always watched," he says.

"Sometimes it is not enough

to be a pure person." He

returned to Egypt, taking

with him a photo of Hussein,

permission from her family

to talk on Facebook, and a

video of her reciting the

Koran. He kept the video

secret for a week, watching

it alone every day. "What am

I to say to my mother? 'I

saw a girl, and I would like

to be engaged with her, and

leave you all?' My family is

not ready for this."

The imam grew up in Itay El

Baroud, a small city on the

Nile Delta. His mother

taught him the Koran. From

five, the little boy would

memorise a passage, go and

play with his friends, while

his mother memorised the

same section – to test him

upon his return. "This

motivated me, this

competition with my mum, not

to make mistakes. She would

say, 'I am working, doing

all my duties in the house,

and memorising better than

you.' She sometimes was

sleeping only two hours. It

makes you feel ashamed if

you are not doing your

best."

Zokm became a childhood

Koran contest champion,

besting as many as 5000

competitors at a time. He

went to Cairo's prestigious

Al-Azhar University, which

for more than 1000 years has

been a beacon for the faith,

representing a moderate

stream of Islam. Hussein

recalls his pledge to her

during their eight-month,

long-distance, online

courtship: "I will never

stop you from knowledge."

They were engaged on Skype,

Hussein in northern

Melbourne's Roxburgh Park

with her family, the imam in

Itay El Baroud with his. The

agreement was sealed by

reading the first page of

the Koran. And then he was

here, married in a tea hall

in front of several hundred

people: "It's something you

never imagine. Being here,

living here, a new wife, a

new life."

Alaa El Zokm sits on a white

leather couch in his yellow

brick veneer home opposite

the mosque. Hussein hands me

a plate of orange wedges,

strawberries and mango, then

sits down. Zokm reaches

across, touches an eyelash

off his wife's cheek, and

blows it away.

They have an easy rapport.

No kids yet. Hussein is

focused on school. In her

third year of a master's

degree in speech pathology,

the workload is heavy.

They met almost three years

ago when the imam first came

for a visit from Egypt,

invited here to consider a

position with the mosque and

a school. "I didn't know

anything about Australia,"

he says. "Nothing. The end

of the earth? Kangaroos?"

His hosts then were wary for

the imam, worried that the

religious leader would

explore Australian streets

and be confused or upset

when passing a raucous

corner pub or a Victoria's

Secret store. He watched

American movies growing up,

however, and so the culture

shock was not so extreme,

even though he remains

steadfast on matters such as

drinking or sex before

marriage. "It's very clear,"

he says. "It's not allowed.

In any way."

Near the end of his trip,

the imam was invited by a

sheikh to meet two local

girls. The Lebanese one, he

was told, was more

religious, and the Egyptian

one more beautiful. Who did

he want to meet?

The imam was stunned. He

went along to a home in

Melbourne's north, however,

and the Lebanese girl was

there, being taught the

Koran. She was shy and did

not look at him. He didn't

look at her, either. They

both giggle at the memory.

"It was very funny!" says

Hussein. "We didn't even

meet! It was so weird. He

was here for three weeks and

going back to Egypt. I was

only 18."

They both thought and

prayed. Hussein had always

wanted to marry an Islamic

leader, and the imam knew

marriage could be

advantageous. "The imam is

always watched," he says.

"Sometimes it is not enough

to be a pure person." He

returned to Egypt, taking

with him a photo of Hussein,

permission from her family

to talk on Facebook, and a

video of her reciting the

Koran. He kept the video

secret for a week, watching

it alone every day. "What am

I to say to my mother? 'I

saw a girl, and I would like

to be engaged with her, and

leave you all?' My family is

not ready for this."

The imam grew up in Itay El

Baroud, a small city on the

Nile Delta. His mother

taught him the Koran. From

five, the little boy would

memorise a passage, go and

play with his friends, while

his mother memorised the

same section – to test him

upon his return. "This

motivated me, this

competition with my mum, not

to make mistakes. She would

say, 'I am working, doing

all my duties in the house,

and memorising better than

you.' She sometimes was

sleeping only two hours. It

makes you feel ashamed if

you are not doing your

best."

Zokm became a childhood

Koran contest champion,

besting as many as 5000

competitors at a time. He

went to Cairo's prestigious

Al-Azhar University, which

for more than 1000 years has

been a beacon for the faith,

representing a moderate

stream of Islam. Hussein

recalls his pledge to her

during their eight-month,

long-distance, online

courtship: "I will never

stop you from knowledge."

They were engaged on Skype,

Hussein in northern

Melbourne's Roxburgh Park

with her family, the imam in

Itay El Baroud with his. The

agreement was sealed by

reading the first page of

the Koran. And then he was

here, married in a tea hall

in front of several hundred

people: "It's something you

never imagine. Being here,

living here, a new wife, a

new life."

|

Alaa El Zokm playing his

weekly post-prayer soccer match

against the young men of the

mosque.. |

The imam speeds away from

the mosque at 7.37pm on a

Sunday night, wearing a

Chelsea Football Club

tracksuit. He's headed to an

indoor basketball court,

part of the Olympic village

from the 1956 Summer Games,

to play a weekly post-prayer

soccer match against the

young men of the mosque.

"The image that comes to

mind for a sheikh or imam is

a hard person," he says,

turning the wheel of his

Mazda 3. "People will try to

be silent, to listen,

because they are afraid to

say something wrong,

thinking, 'I can't joke with

him. I can't ask him to come

play PlayStation.' And it is

not true. The religion is

not what will keep you from

enjoying life. If this was

the religion, I would never

follow it!"

But is he any good with the

round ball? "You will see,"

he says, smirking. "I don't

want to talk about myself."

The guys are already on the

squeaking wood surface under

big industrial globes, and

soon the imam is among them,

loping after the ball like a

lost giraffe. But then he

kicks, and he has a cannon.

He fires shots from all

angles and the ball thuds

against posts and bodies. He

does not often pass.

"Stop shooting!" yells one

player, laughing.

"Oohhh Alaa!" cries another,

as the imam attempts a

speculative strike.

"Goon hayel!" jokes one

spectator. (Arabic for

"great goal", it is said

sarcastically.)

Yet he scores five goals in

90 minutes of the three-hour

game. As he walks off court

he is patted on the back by

Khaled Elkharibi, 21. "He

just demolished half our

team," says Elkharibi. "Five

goals in a 15-goal game. And

he only came in halfway."The

radicalisation of young

Islamic men is, naturally, a

concern for the imam. But he

has never known anyone to

take up arms on behalf of

Allah. Hussein believes most

who do so are in fact

"converts" to the religion.

"They have no knowledge of

Islam," she says. "They

drink, they eat pork, they

don't go to our schools, but

they have the beard and

white clothes."

The imam points the finger

at chronically

misinterpreted phrases

within the Koran. "Jihad" is

just one example. There are

also passages that note

whoever is killed for his

country will be rewarded in

paradise: "But this was from

a time when Islam was under

siege.

"Sometimes they go down this

path for benefits," he adds.

"They are promised wives or

money or jobs by Islamic

State, so they hide what

they have in their minds."

It is a perfect spring

evening in Melbourne;

sunshine pours through the

high windows of the

Government House ballroom,

striking a crystal

chandelier above the imam,

who sits in the third row of

a large gathering.

A school orchestra is

playing, bouncing prim notes

off gilded walls painted

with fleurs-de-lis. There

are police, women in saris

and tall Sudanese men,

gathered for the Victorian

Multicultural Awards for

Excellence.

Speakers drop encouraging

multiculturalism buzz-words:

cross-cultural empathy and

social harmony, diversity

and diaspora. Maoris with

spears perform the haka:

"The harder we go, the more

we feel, the greater the

respect," says one. "We hope

you feel respected." The

imam nods.

The imam receives a Police

Community Exemplary Award,

recognising the work of the

mosque through open days,

volunteer efforts, Iftar

dinners and Eid festivals.

The imam looks resplendent

in an ankle-length coat, the

kakola, and his hat, the

emma – the distinctive

uniform of his alma mater in

Egypt.

He wears such garb in

public, too, at supermarkets

and petrol stations. He has

never been abused – "Perhaps

because I am big" – but does

notice people laughing at

him sometimes, or looking

worried. Yet he enjoys going

into shops – even when he

senses he is being watched.

"They may be thinking, 'He

has a bomb.' Let them have

these thoughts," he says.

"Because when you smile, and

leave, and everyone is safe,

you will change these

thoughts."

The evening turns to

Vivaldi, canapés, champagne

or, in the case of the imam,

apple juice. Inspector Anne

Patterson, the local police

commander, looks on as he

poses for photos by a

lamp-lit fountain. "Isn't he

wonderful?" she whispers.

"He's incredibly progressive

as a thinker. I really like

his central messages, about

community harmony, the faith

not being inconsistent with

the Australian way of life.

Even delivering his messages

in English – realising that

sometimes when they're only

delivered in Arabic it can

isolate others."

The latter gesture is not a

simple one, either. English

is his second language. When

the imam first arrived, he

would write his speeches and

Hussein would translate

them, and he would read

English directly from the

sheet. And then he stopped.

He thanked his wife for her

help, but decided to speak

from the hip, even if it

meant mistakes. "I was so

scared when he said that,"

says Hussein. "I was like,

'What if you stuff up? What

if you need help?' I can't

be there, because I'm

upstairs with the women.

Then the first time he did

it, I said, 'That's it,

we're never going to do a

translation again, because

this is perfect.' "

They depart quickly, riding

home in a police car. He is

happy the windows are

tinted, he jokes, so no one

can see inside: "Otherwise

our community will think

that we are arrested!"

|

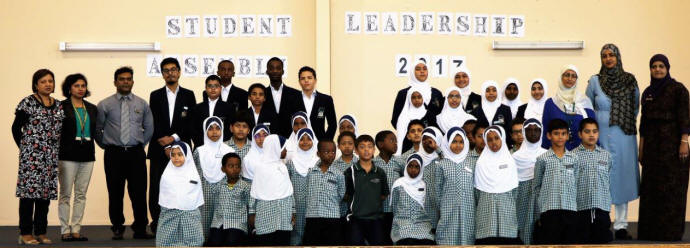

Imam Alaa El Zokm teaching an

Islamic studies class at the

Australian International Academy

in Coburg North. “I teach them

that God loves them,” he says,

“rather than saying, ‘If you do

this you will go to hell’. They

are little bodies who want to

enjoy life.” |

It's Wednesday morning, the

first week in November, the

day after the Melbourne Cup,

and the imam sits on grey

carpet in the corner of a

little mosque at the

Australian International

Academy of Education – an

Islamic primary school. He

is part of a circle of 15

year 2 students wearing blue

jackets and maroon jumpers,

with plastic heart bracelets

and purple Swatches. They

are discussing love.

The imam has taught before

at schools in the Middle

East, most notably Saudi

Arabia. He saw much there

that confused him, such as

women not being allowed to

drive. "If you say, 'This is

the policy of the country,'

I will accept this – this is

your rules, your law – but

if you try to make this an

Islamic thing, this is

wrong," he says. "She has to

go outside – that is normal

life."

In Australia, the imam

shields children from

stringent lessons about what

is lawful and not. "I teach

them that God loves them,"

he says, "rather than

saying, 'If you do this you

will go to hell.' They are

little bodies who want to

enjoy life."

He teaches through

brainstorming, reflection

and practice. ("I teach them

how to discuss," he says,

"not to know.") And today

the lesson is the mosque

itself – a place most have

never really been before.

They are incredibly excited.

With each question the imam

asks, arms shoot high and

the kids – like Jumanah,

Salman and Fatima – squirm

onto their knees, contorting

their tiny forms, desperate

to answer.

He asks first, "What do you

know about the mosque?"

You have to be very quiet?

You can't talk while the

sheikh is reciting the

Koran.

It's a place you pray.

It's where we read the

Koran.

You come to the mosque so

Allah can take away all your

sins.

"Excellent," he says. "We

come to the mosque because

everyone is making mistakes.

And we come to ask

forgiveness."

It's where we tell the

truth?

"Yes, but we say the truth

everywhere, don't we? We say

the truth at home, outside.

Always."

He explains why the mosque

is called "Allah's house".

He talks about why the lines

on the floor face Mecca, and

why congregants line up:

"What does it teach us?"

To not be racist?

"Yes, can you explain this?"

Because if you are a white

person you might be sitting

next to a brown person?

"That's right," he says.

"The Prophet is teaching us

equality. There is no

difference between the

person who comes from

Pakistan or India, from the

rich person and the poor

person."

|

Imam Alaa El Zokm at the

Australian International Academy

in Coburg North last November.

|

Near the end of the lesson

he waits for silence – "I am

going to stop until I see

everyone is quiet!" – and

assembles the children in a

line. They remove their

Bonds socks and Hello Kitty

socks, and he sends them to

the ablution room one by

one, the quietest child

first. There he explains how

to make wudu – cleaning the

hands, face and arms, wiping

your head, ears and feet in

preparation for prayer. They

scurry back into the mosque,

damp and squealing "I'm

soaking!" and "That was so

easy!" and "Time to pray!"

Leyla Mohamoud, the head of

the campus, says the imam is

the perfect teacher for

spirituality. She wants to

show me the school, too, and

explain how they have footy

days, and ties to local

scout groups. She points to

photos from Halloween, when

the kids came as vampires

and chefs and superheroes.

The tour ends in the art

room, where the walls are

covered in drawings of

smiling faces.

The imam points to a pencil

sketch of a smiling girl

with green eyes. He notes

that in other parts of the

world, such a picture could

not exist. "It is

forbidden," he says, looking

into the rendered face, and

shaking his head. "But these

eyes are beautiful."

|

Alaa El Zokm sharing chores

with his wife, Rheme. “This is a

problem with the husbands,” the

imam says. “They do not help.”

|

A few weeks later, the imam

is standing in his home's

backyard. Amid the overgrown

grass and daffodils, a Hills

Hoist stands in the corner.

The imam pins a pair of wet

tracksuit pants to the line.

"This is a problem with the

husbands. They do not help,

do not share the work," he

says. "They think the

woman's role is to stay in

the home and do everything.

That is not Islam."

Such behaviours are, he

says, habits. Bad ones. This

was the subject of his

speech only an hour earlier

at the mosque: What is

Islam, what is faith, and

what is not?

While there are no great

schisms within the mosque,

there are local Sunni who do

not want to sit with the

Shia. There are those who do

not believe that eliminating

Islamophobia is the

responsibility of those who

follow Islam, but those who

have the phobia. "Some of

them come angry, and I have

to absorb their anger," the

imam says, grasping the air

in front of him, and drawing

it to his chest. "I listen,

smile. I find a verse of the

Koran, something common

between us."

He pins a final T-shirt to

the line, and a rainbow

lorikeet rests on a

lemon-scented gum nearby.

"We believe that this is our

job – our mission in life,"

he says, as the bird sings

into the day. "If we don't

do this, then later we will

be asked by God, 'What did

you do with the message you

had?' If we don't spread

this message, we will not

prosper. If we don't do

this, then who will?"

Source:

Sydney Morning Herald

|

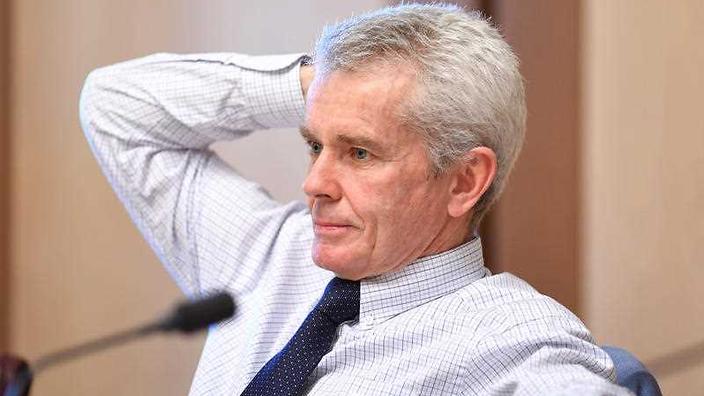

The

SBS Board and Executive

today welcomed the

appointment of Dr Bulent

Hass Dellal AO as the SBS

Chairman, as announced by

the Minister for

Communications, Mitch

Fifield.

The

SBS Board and Executive

today welcomed the

appointment of Dr Bulent

Hass Dellal AO as the SBS

Chairman, as announced by

the Minister for

Communications, Mitch

Fifield.

Grab

our essential pack and start your fitness journey today

Grab

our essential pack and start your fitness journey today